Spanglish Literature | Latinx Vanguard

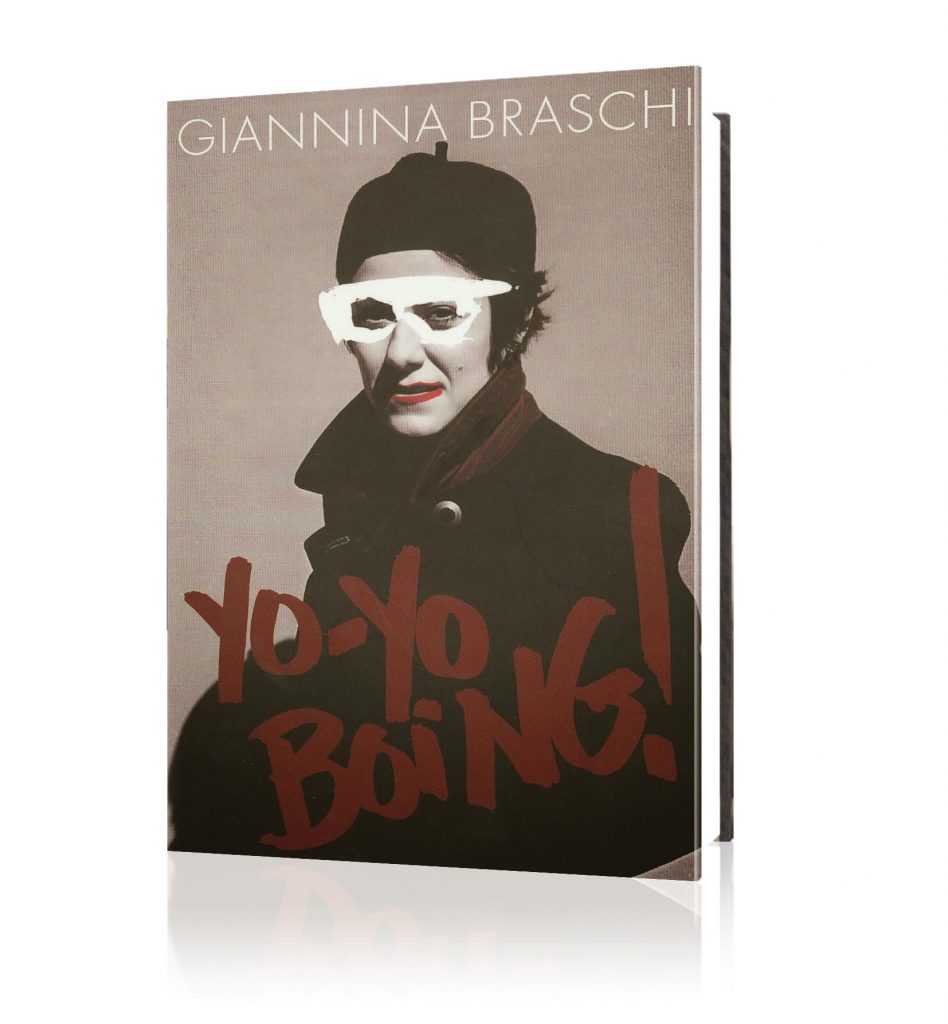

Yo-Yo Boing!

An excerpt from

PART II. BLOW-UP

The era of the generalist is coming back. The specialist is dated. The nose specialist, does he consider your eyes, your mouth, your aura, your personality, before he breaks your nose and turns you into another chiguagua. No, he goes cross-eyed staring at your nose. Jack of all trades–the specialist diminishes the value of knowing it all, or at least, trying to grasp it all, and adds–Master of none. Un especialista, just for discerning the details, is not un sabio. El sabio puede ser un necio. Mira lo que decía Alcibíades de Sócrates, borracho, en las tabernas, bebiendo vino, con los dientes podridos. Mistaken for a beggar. How can a wise man look so base? Las apariencias engañan.

– No engañan, my darling, confunden. If I say–here, pretzels, here, porn films, here, sexy bodies–then, they will flock to me–looking for cheap thrills, thinking I am another Madonna, but in the middle of my show, I’ll play a trick on them, as they have been playing tricks on me. Saying it’s great, when it tastes like shit. I’ll do the opposite. I’ll dress like a slutty punk, but I’ll give them the real thing, and I don’t mean coke. I’ll give them poetry.

– What kind of poetry do you write?

– What do you mean?

– I write sonnets, and you?

– I can’t fit life into rhyme scheme. It would be a strait jacket. Rhythm is free. How can I accept rhythms of ancient ages when I’m feeling my own rhythm. The velocity of cars – the engines of our time – concords, faxes, guns and subways. The way we talk and the way we commute. Do we have time to write novels. What is immortal in a novel is not the form which is long dead, but the context. And the same with poetry – what is said – that remains, the way we say things, changes.

– Which means, you write blank verse like Neruda.

– No verse.

– Like Rimbaud–or Baudelaire–Little Prose Poems?

– I write big books. Which is not to imply that I like everything in them.

– Then why do you publish them?

– Because it’s not a matter of liking. Because to tell you the truth, many times, I don’t like myself. What am I going to do? Kill myself because I don’t like myself. No, I exist. Those poems I do not like function in the whole work. And they work well. So, it’s not a matter of liking. I don’t like my nose, but it exists and it works well.

– You could also get a nose job.

– Why, I can breathe.

– Do you write every day?

– I don’t have something to say every day.

– I always find something to say. I have the feeling we are very different poets. I’m sure Suzana told you that I won a poetry contest at the Poetry Society of America. It had an environmental theme. What do you write about?

– I don’t have themes. I have flavors like Bazooka. My favorite is the pink one. I love to suck all the sugar out of the pink one.

– Flavors don’t last, especially Bazooka. Poetry has a mission and I take my role very seriously.

– So do I. I want poetry to be a fashion show–to have a taste of frivolity–savoir faire–a taste of time at its peak–Kenzo, Gigli and Gaultier. I’m more excited by Bergdorf ’s windows than the contemporary poetry I’ve read.

– Who have you read?

– I don’t read any of them.

– It shows. You must realize you’re limiting your audience by writing in both languages. To know a language is to know a culture. You neither respect one nor the other.

– If I respected languages like you do, I wouldn’t write at all. El muro de Berlín fue derribado. Why can’t I do the same. Desde la torre de Babel, las lenguas han sido siempre una forma de divorciarnos del resto de la humanidad. Poetry must find ways of breaking distance. I’m not reducing my audience. On the contrary, I’m going to have a bigger audience with the common markets–in Europe–in America. And besides, all languages are dialects that are made to break new grounds. I feel like Dante, Petrarca and Boccaccio, and I even feel like Garcilaso forging a new language. Saludo al nuevo siglo, el siglo del nuevo lenguaje de América, y le digo adiós a la retórica separatista y a los atavismos.

Saluda al sol, araña, no seas rencorosa. Un beso,

Giannina Braschi

“A tour de force, not only because of its linguistic sophistication but because of the cognitive demands it presents the reader.”

Christopher González (Permissible Narratives: The Promise of Latino/a Literature)

Adaptations and Translations of Yo-Yo Boing!

Yo-Yo Boing! was first published as a literary and linguistic hybrid in Spanish, Spanglish, and English by Latin American Literary Review Press (1998). The work has since been published in various editions and formats, including an English translation by Tess O’Dwyer (AmazonCrossing, 2011).

Excerpts have been widely anthologized and applied to diverse fields of teaching, from courses in literature, philosophy, and linguistics to books on Hispanic culture, globalization, and design thinking.

As an indication of range, artists such as Michael Zansky have quoted Yo-Yo Boing! in their paintings, and passages appear in Mohsen Mostafavi’s architectural project Urbanismo ecológico en América Latina (Harvard University Graduate School of Design/GG, 2019).