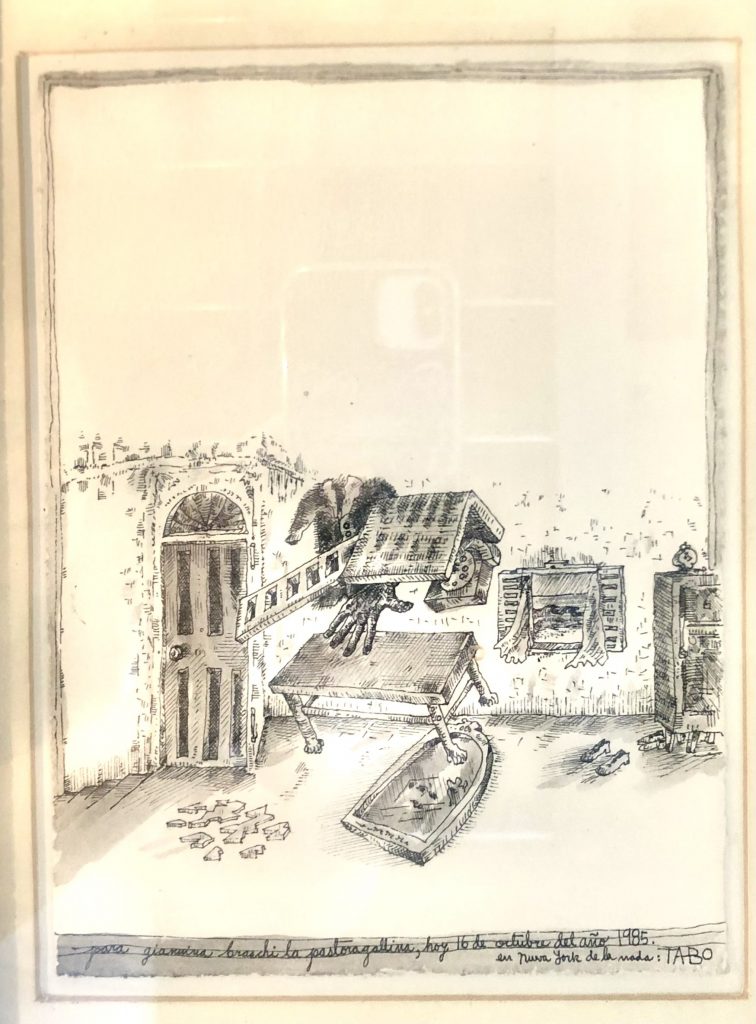

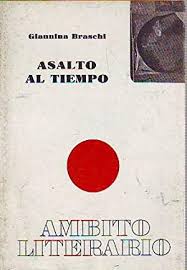

Latin American Poetry and Magic. Here Laura R. Loustau analyzes the transformative power of Giannina Braschi’s first book of poetry Asalto al tiempo (1981). The following excerpts are from Loustau’s chapter “The Poetry of Giannina Braschi; Art and Magic in Assault on Time” which first appeared in the anthology “Poets, Philosophers, Lovers”.

The Poetry of Giannina Braschi: Art and Magic in Assault on Time

EXCERPT #1

“I want people to feel transformed after they have read me. I want them to memorize me because that is how I write. To be memorized. To be learned by ear. To be learned by heart,” said Giannina Braschi in an interview on the transformative power of poetry (Rivera). Asalto al tiempo (Assault on Time), Braschi’s first work of poetry, was originally published in 1981 and later became part 1 of the trilogy El imperio de los sueños (1988) translated into English by Tess O’Dwyer as Empire of Dreams (1994).1 I am interested in identifying instances that unravel a transformational Braschian poetics that speaks to the author’s desire for the reader (and the poet) to become transformed through the acts of reading and writing.\

In “Breve tratado de la poeta artista” (Brief treatise of the poet- artist), a text that articulates the author’s own vital and transformative philosophy, Braschi proposes the concept or figure of the poet-artist. The poet-artist has three beings within: the poet-child who feels, the poet-philosopher who thinks, and the poet-actor who transforms. In the framework of poet-artist, the repetition of the child coexists with the transgression of the philosopher and the metamorphoses of the actor (469). For Braschi, “the child poet is the one who discovers the magic and, above all, the surprise . . . s/he is the one who opens the Pandora’s box” (472).

In the first poem of Assault on Time, the poet-child opens a door to surprise and invites the reader to imagine an animated play space:

“Behind the word is silence. Behind what sounds is the door. . . . But if I ring the bell, water jumps, and a river falls out of the water again. . . . And suddenly everything acquires movement. Two travelers meet and their shoes dance. And breeze and morning clash. And the seagull runs and the rabbit flies. And runs and runs, and the current ran. Behind what runs is life. Behind that silence is the door” (3).

Giannina Braschi, Assault on Time

Like the world in María Elena Walsh’s songs, this scene lures us in to a game of wonder and imagination.2

According to Puerto Rican philosopher Francisco José Ramos, Braschi’s poetry “offers us a delicious opportunity to rethink words and em- bark upon a journey through the images seen with the eyes of a child.”3 This statement about the importance of seeing can be paralleled with the ideas of Gaston Bachelard, who argued that the real can be explained by the imaginary. For Bachelard this relationship consists not only of form- ing images but of transforming them with great agility: “imagination, more than reason, is a unifying force in the human soul” (190).

Braschi’s treatise qualifies Lorca and Vallejo as the best examples of the poet-child in twentieth-century literature. Their fame, notes Braschi, “was not established through covert intrigues or literary contacts—what enabled them to triumph was authenticity… feeling… poetic nature . . . [and] the passions of the soul” (“Breve tratado” 474). Braschi sees in them that “poet-child” who condenses the ancient, what belongs to human nature, and reconfigures it to act as transformative agent (474). The influence of César Vallejo’s poetry—particularly The Black Heralds and Trilce—on Braschi’s work is palpable. As she stated in an interview: “Vallejo is a jack-in-the-box who performs the movement of my spirit. No matter how much you push him down into the box, the poet always bounces back to affirm his love for life.”4 It is interesting to consider how these canonical texts can be revisited and reappraised after reading Braschi’s poetry and her brief treatise (Morris).5. (Continue here.)

Poetry Magic Art

(Excerpt #2 about poetry magic art.)

Braschi has described Empire of Dreams, Yo-Yo Boing!, and United States of Banana, her three main works, as “stages in my life, like Goya’s Black Paintings or Picasso’s blue period,” while also noting that she “depicts (and inserts) herself, much in the way that Rembrandt did in his works” (Díaz). These allusions to art have tempted us to find pictorial references in Braschi’s poetry, as well as poetic references in the work of the Spanish Mexican artist Remedios Varo, whose paintings are in- fused with dream and travel imagery.7 Varo’s paintings include gothic buildings, androgynous beings, insects, stars, nocturnal forests, spinning objects, hermetic and dreamlike worlds, as well as levitating beings. Similarly, Assault on Time is composed of dreamworlds where a series of real and illusory routes and desired and imposed escapes are constructed and deconstructed.

The appearances, disappearances, and the loss of gravity are as germane to Varo’s paintings as they are here in Braschi’s poem: “The wind and I would have to take off and fly. Behind the closets and under the furniture no one says my name. Yes, I know I’m in a world of invisible sounds. I know its origin. I go toward it and hide. The wind and I would have to take off and fly. My hand says it no longer feels the air” (ED 12). The speaker yearns to rise and take flight with the wind. This desire to fly is repeated in the first and fifth lines, underscoring the urgency and yearning of the poetic self. The speaker aches to fly, understand the world she inhabits, recognize her origins, and heed what her hand has to say. However, the poem contrasts the images of presence (“I know”) with those of absence (“no one says,” “I hide,” “no longer feels”). It is a game of hide- and-seek fueled by inspiration (the alluring promise of soaring skyward). Yet the images slip away, the poetic voice escapes, and the body feels, in its disembodied flesh, an absence, though temporary, of the inspiring muse.

For Bachelard, allusions to air in poetry are fundamental because “Through [the air], life and movement are possible” (64). Air acts as “a material element . . . is the principle of a good conductor that gives conti- nuity to an imagining psyche” (17). He explains that what is comforting about these air images is that, by feeling connected to them, we become aware of a sense of release, of great joy, of weightlessness (20). In Braschi’s poem, however, the reader may not so easily find such an ecstatic sen- sation of release. Instead, we become ensnared in a nomadic enterprise with departures and retreats that impel us to travel along with the poet through an infinite series of spaces and times:

And among countless roads and old shoes, among countless objects and questions, the hand acts as an interpreter and the air keeps blowing and the door keeps unlocking and the wind goes back to its place as the door closes. Yes, everything has its place and everything counts when objects empty at the door. But I feel there is something weightless that runs. It’s something that rises and never reveals itself and has to hide in some other corner. And that something now raises the same questions. And the wind finds itself back at a point—right where silences fly and objects jump back into the painting. But by then you can’t tell one object from another—it’s as if they weren’t the same objects: watch, mirror, image, wind. But my hand knows the fall, and there’s no other question than the same objects striking the frame and the chair. And the air stays still and everything is in its place. (12)

Here the poet becomes a painter, who traces with her pen images and ideas that travel and move. Likewise, the poetic voice depicts herself as a poet-artist, one who ambles incessantly and who becomes this very process of searching.

In another poem, the poet arrives at a house “transformed into art,” in which memories are neither romanticized nor defined (ED 16). Here, the poet-artist plays with the “frame” of a painting, like the frame of a house, and with the “lintel,” that horizontal piece above doors and win- dows that supports weight loads:

I arrive at your house transformed into art, framed by my memories. The lintel’s color is the guardian of my dream, you the painting. The frame of your house crosses the bottom of the painting. I cross the horizon and sit down to look at it. I arrive home transformed into art, framed behind your memories. (16)

The speaker tells us about memories and wooden structures that frame objects and dreams. If we reflect upon the progression, we realize that, at the beginning of the poem, the poet arrives at the house “framed by my memories,” yet by the end she is “framed behind your memories”

The image of the poet entering and leaving a painting reminds us of the poem “Remedios Varo’s Appearances and Disappearances,” in which Octavio Paz alludes specifically to the artist’s sensibility: “With the in- visible violence of wind scattering clouds, but with greater delicacy, as if she painted with her eyes rather than with her hands, Remedios sweeps the canvas clean and heaps up clarities on its transparent surface” (Alter- nating Current, 45). Paz describes the magical worlds of the artist, worlds where beings and objects levitate and become weightless, as “laughter [that] echoes in another world” (46). According to Paz, Remedios does not paint time but the moments when time is resting. One of the most powerful lines of the poem is when Paz states that Remedios “surprises us because she paints surprised” (Corriente alterna, 51).8 In each poem of Assault on Time, as in each of Varo’s paintings, seemingly senseless logic becomes a language of its own, whose essence is ephemeral. Both artists deploy a playful charm that engages and entrances, and yet, despite their levity, there is a nagging feeling of solitude…

For the full essay by Laura R. Loustau, click here.

Poetry impels us to endure the mystery; it beckons us to follow blindly into inclemency and faith. Faith in the other, without whom I do not exist, yet also with whom I can never be eternally. That is where the poem intercedes.

Diana Bellessi

Latin American Magic and Poetry Essays

- Ahmad, Sarah. “A Big Solitude: A Conversation with Giannina Braschi”. Poetry Foundation. (2022)

- Sorrell, Martin. “The Magic Mirror of Literary Translation: Reflections on the Art of Translating Verse. By Eric Sellin.” French Studies (2022).

- Noheden, Kristoffer. “Magic language, esoteric nature: Rikki Ducornet’s surrealist ecology.” Surrealist women’s writing. Manchester University Press, 2021. 225-245. Latin American Poetry Magic Art.

- Loustau, Laura R. “Nomadismos lingüísticos y culturales en Yo-Yo boing de Giannina Braschi.” Revista Iberoamericana 71.211 (2005): 437-448. Latin American poetry magic art.

- Karimov, Ziyoakhmad. “MAGIC REALISM IN WORLD LITERATURE.” Mental Enlightenment Scientific-Methodological Journal 2022.1 (2022): 119-128.

- Loustau, Laura R. “The Poetry of Giannina Braschi.” Poets, Philosophers, Lovers: On the Writings of Giannina Braschi (2020): 34.

- White, Rachel. “Early Modern Literature and the Occult.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. 2022. Latin American Poetry Magic Art

- Click here to read the Loustau’s complete essay on magic and poetry in Assault on Time in Giannina Braschi’s Empire of Dreams. (On Latin American poetry magic art)

- Matinez Capo, Juan. Asalto al tiempo, Giannina Braschi. EL MUNDO (1981).

- Loustau, Laura R. “Sal de sangres en pánico by Alicia Kozameh.” Confluencia: Revista Hispánica de Cultura y Literatura 37.1 (2021): 179-180.

- Loustau, Laura R. “Nomadismos lingüísticos y culturales en Yo-yo boing de Giannina Braschi.” Revista Iberoamericana 71.211 (2005): 437-448.

- Loustau, Laura R. “Cultures of Surveillance in Contemporary Cuba: The Literary Voice of Yoani Sánchez.” International Journal of the Humanities 9.6 (2012).