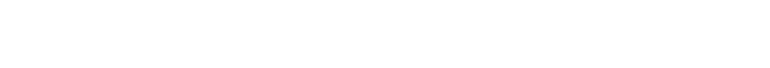

“United States of Banana: A Graphic Novel” a book of liberation and becomings

Review by Rolando Perez for Latinx Spaces.

United States of Banana: A Graphic Novel is an artistic event, the result of a collaboration between Puerto Rican writer Giannina Braschi and Swedish cartoonist Joakim Lindengren. In effect, it is the graphic novel version of Braschi’s 2011 eponymous genre-bending book. In part prose poem, narrative, and play, United States of Banana is the performance of something completely new: a language of indistinctions and liberation from binarism that recalls Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil. “I was born after the distinctions were made, so I don’t distinguish between la chicha y la limonada, el merengue, y el coquí,” says the character of Giannina in United States of Banana (135). And thus, to that end, the graphic novel masterfully captures Giannina Braschi’s deconstructive ontology, epistemology, politics, and ethics.

This geopolitical tragicomedy is part of the Latinographix series at Ohio State University Press, edited by Frederick Luis Aldama (a.k.a. Professor Latinx), who has who has done more to advance Latinx superhero comics and Latinx graphic novels than anybody else—through his scholarly optics as well as through his Latinx Pop Lab at the UT-Austin. Masterful titles in the graphic novel genre-at-large include Angelitos: A Graphic Novel by Ilan Stavans (author) and Santiago Cohen (illustrator) (2018); The Trial: A Graphic Novel by Franz Kafka and Chantal Montellier (illustrator) and David Zane Mairowitz (adapter) (2008); Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel (2007); The Witch Owl Parliament (Clockwork Curandera) by David Bowles and Raúl the Third (authors) and Stacey Robinson and Damian Duffy (illustrators) (2021); and, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale by Art Spiegelman (1986).

Now, in comparison with some of the above-mentioned texts, the last two, Maus and The Witch Owl Parliament stand out as novels of becomings. In Maus Jews become mice, and thereby overturn Hitler’s statement at the beginning of the book that Jews are not human, and in The Witch Owl Parliament (which takes place in the Texas-Mexico border), the main characters of this children’s graphic novel (Cristina, Enrique, and Mateo) possess transformative, indigenous superhero powers. In such becomings, the ontological categories of what is and what is not human are deconstructed and withdrawn from the traditional Aristotelian hierarchy. Thus, in this sense, Maus, The Witch Owl Parliament, and United States of Banana, can be seen as works of becoming, independence, and freedom that challenge the violence of stasis, borderlands, Sameness, and the imposed categories of race, gender, and nationality kept in placed by the forces of colonization and empire.

As such, Joakim Lindengren who has profoundly understood the original text, doesn’t miss the opportunity to parody Guy Peellaert’s brain-twisting cover illustration of David Bowie’s 1974 album Diamond Dogs. With Lindengren the becoming-dog of Bowie (with genitals) is replaced with the becoming-dog of an androgynous Hamlet, except that instead of two women in the background we now see Segismundo peering from behind (66). “The best of both worlds” reads the caption that exemplifies Braschi’s mestizaje, where one does not have to choose between a false A and B, and so incipit the comedy where Giannina, Hamlet, and Nietzsche’s Zarathustra come together, first in the 2011 novel and then in Lindengren visual’s rendition of their encounter.

Here we see Hamlet and Zarathustra carrying dead bodies on their backs into the Fulton Street Market (Braschi’s allusion to the “Flies at the Market-Place” in Thus Spoke Zarathustra), and Giannina carrying a coffin-shaped backpack-sardine can with a cross on it where the dead sardine lies. Hamlet appears in the garb of seventeenth century prince; Zarathustra, as a bearded, decrepit old man, donning a Superman outfit (an allusion to Nietzsche’s ubermensch, sometimes translated as “Superman”), and Giannina in contemporary attire (below).

This opening scene of the graphic novel (which is not the start of the original) bears the title “Burial of the Sardine”. And the choice of beginning the graphic novel with it is significant because there is no moving forward, no ferry trip to Liberty Island, until the smelly sardine that is “the 20th century” with all its horrors has been buried, for though Giannina says otherwise, it was a century of mass genocides. “When I said I will bury the 20th century—everybody—not just me—went looking for a dead body,” says Giannina (5). “Burying” the twentieth century much like the announcement of the “death of God” is interpreted literally, and yet, there is something quite literal about it, like Lindengren’s realistic depiction of the Fulton Market in New York City, where not too far from it the Twin Towers fell on 9/11. For after all, United States of Banana is a post-9/11 text, fragmented, as all the fragments (glass, paper, torsos, body parts) that came down that day.

Unfortunately, however, the 20th century is not dead. When Giannina opens the sardine-coffin she finds that the “ugly” sardine is still moving (3) and begs not to be buried alive (4). Later in a parodic panel of Da Vinci’s The Last Supper, Giannina sits on one side of the table with Hamlet, while Zarathustra sits on the other side. But significantly no one occupies the center position as the redeemer has died. “We are gathered here to break bread with our dead bodies,” declares Zarathustra (6). And when Zarathustra asks Giannina, “do you believe in liberty?” she answers: “As much as I believe in God, in Santa Claus” (7). Not Zarathustra, not even Hamlet can be of any assistance; obsessed with ghosts, he looks only to the past. Full of the heaviness of “ressentiment,” he is not a bridge to anything; and as they leave to embark on the ferry, they go past a bar, full of people, with a large bay window, that is a parody of Hopper’s Nighthawks (1942). Here Lindengren has replaced the original name of the bar (“Phillies”) with the word “Philistines.” The alienation and isolation in the crowded bar are complete.

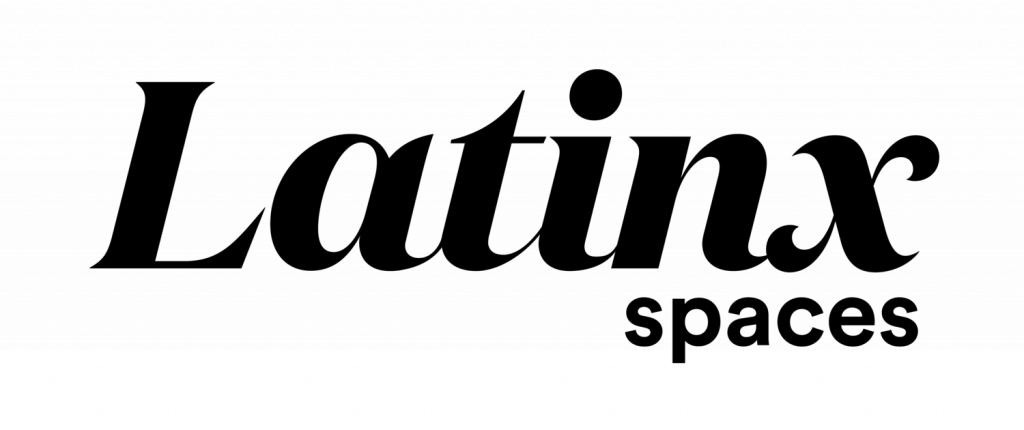

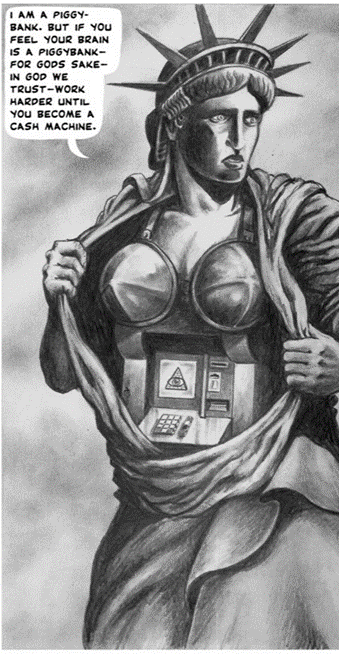

In the section that follows, we encounter the Statue of Liberty tired of being a statue. “I have inspired empires. I have destroyed empires,” she says (8), with an air of boredom. “They turned me into the mausoleum of liberty,” complains the statue, bringing to mind the Nicanor Parra’s artefact, where beneath a drawing of the Statue of Liberty appear the words: “USA, where freedom is a statue” (below).

The Statue’s social security number is 009-11-2001, “the day the towers fell” and she began to shrink (10). And the panels that follow make impactful allusions through both photography and the history of art to some of the horrors of the twentieth century. In one panel Lindengren foregrounds the famous Nick Ut photograph (The Napalm Girl, 1972) of a girl running naked after being burned in Napalm attack in Vietnam, and in the background smoke billowing from the Twin Towers.

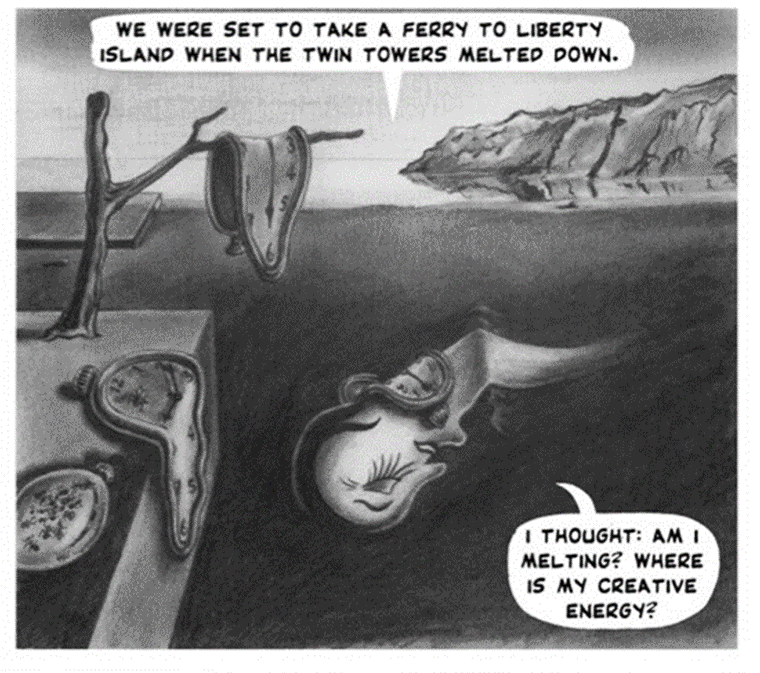

In another Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931) is parodied with the words “We were set to take the ferry to Liberty Island when the Twin Towers melted down” (13, below), and in various panels disintegration, sadomasochism, and the exploitation of bodies are depicted through references to Francis Bacon (14), Hans Bellmer bound dolls, and Bettie Page photographs (24).

Now, when Giannina asks the Statue, who has become a piggybank and a cash machine (below: because in “the United States of Banana everything is for sale,” 16) what her expiration date is, the Statue responds: “The day Segismundo takes the crown’ (10).

For Zarathustra Segismundo “is the overman,” for Giannina, “a poet,” and for Hamlet “a conqueror” (10). Regardless, this takes us to “Under the Skirt of Liberty,” one of the most satirically profound sections of United States of Banana: (33-56), for here we encounter a glimmer of hope offered by decolonization in all its forms.

Segismundo, the protagonist of Pedro de Calderón de la Barca’s play, Life is a Dream, has been “living in the dungeon of Liberty” (34) for more than one hundred years. In this Spanish Golden Age play, King Basilio of Poland locks away his son, prince Segismundo, at birth, because the boy has been prophesied to destroy the kingdom someday in the future. It is in this sense that Segismundo and Hamlet are “brothers” for Braschi, and that their literary parents, Basilio (Segismundo’s father) and Gertrude (Hamlet’s mother) later marry in the “Wedding of the Century” (57-68). And, if in the first iteration of Da Vinci’s Last Supper, there was no one at the center of the table, this time Segismundo takes center stage (34). For more than a personage, Segismundo is a force, a world, a country. Segismundo is a Puerto Rico that for more than a century has been under the sandals of the Statue of Liberty (96), but which at last wishes to be independent and free in a Latin American sense. Braschi writes:

“Segismundo thinks that he depends on liberty, but the truth be said—liberty has more need of him than he of the of the statue…The people want to liberate him. Especially his own people—immigrants and prisoners from around the world. So in order to prevent the coming insurrection, a voting system is created to give the people the impression that Segismundo’s destiny is in their hands.” (7)

This is how the United States of Banana’s theater of freedom and democracy functions: a traffic light with a button that says: “press to cross,” but nothing happens. The light changes when it is programmed to do so. But the people are “given” three options, writes Braschi: Wishy, Wishy-Washy, Washy. She continues:

“If they vote for Wishy [independence]—Segismundo will be liberated from the dungeon. If they vote for Wishy-Washy [commonwealth], the status quo will prevail. If they vote for Washy [statehood], he will be sentenced to death, and nobody will have the honor of hearing his songs rise from the gutters of the dungeon liberty. Every four years the citizens of Liberty Island vote for Wishy-Washy. They can choose between between mashed potato, French fries, or baked potato. But any way you serve it, it’s all the same potato.” (7).

United States of Banana

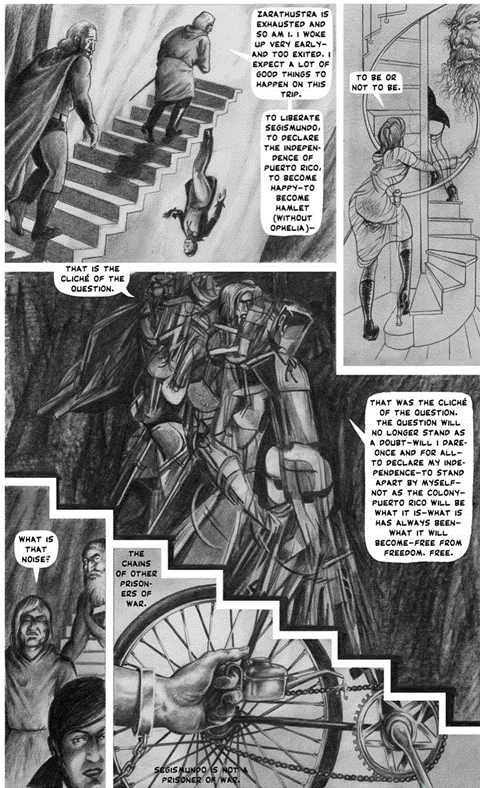

No wonder, then, that Giannina repeatedly says that she does not believe in freedom, in a country where, as Parra would say, liberty is nothing more than a statue. “Freedom is a demagogue, I am a warrior,” says Giannina to Zarathustra in the graphic adaptation (22). She doubtlessly says this in response to the Statue’s earlier statement that as a trophy and the spirit of the French medieval warrior, Joan of Arc, she “liberated France from Anglo-Saxon freedom,” the very notion of freedom that Giannina refuses to believe in. This individualistic concept of liberty is what has kept Puerto Rico (Segismundo) imprisoned in the dungeon beneath the skirt of the Statue of Liberty. In a monologue in United States of Banana Segismundo declares: “I have to separate myself from your expectations, so that I can claim the liberty to be free from an associated state. The freedom I will claim is an interior freedom, but that freedom which I have inhabited for a long time, will blow Puerto Rico’s mind out of the association that has harmed its sovereignty” (178). And in the graphic novel, the Statue’s own desire to become “free from freedom. Free,” is succinctly captured in a parody of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (1912, below).

Here at last, the emperor has no clothes, and the only way for Puerto Rico (like Hamlet) to gain its independence is by sending the United States of Banana, “to the nunnery.” In one of the many renderings of Escher’s Relativity (1953), Zarathustra and Hamlet are shown ascending a staircase while Giannina descends it upside, and the caption reads: “To liberate Segismundo, to declare independence of Puerto Rico, to become happy—to become Hamlet (without Ophelia)” (29, below), that is what is necessary for new beginnings.

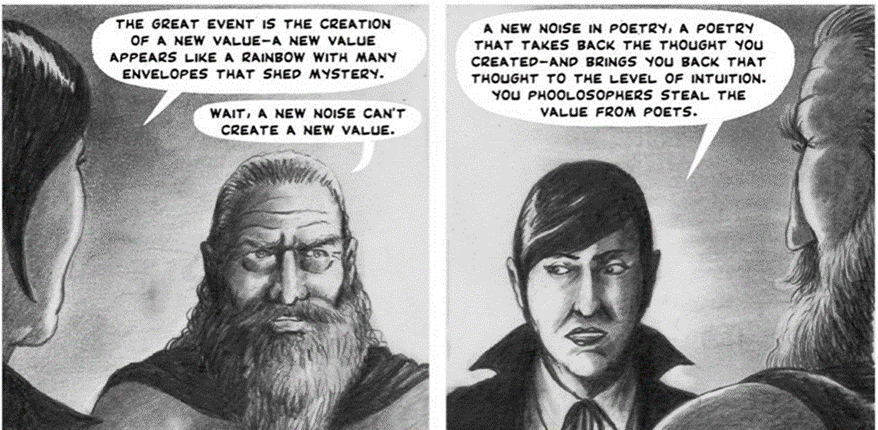

In the end, the liberation from the United States of Banana where Giannina, Zarathustra, Hamlet, and Segismundo float away on the crown the Statue has hurled into the river, can only take place because Segismundo is able to put himself “in the shoes of the other” (40) and dance (the Nietzschean dance) wearing stockings and high heels (49): in a new world where “genders like genres are melting like the seasons. The borders are no longer effective in underlining distinctions between melodrama and drama” (42). It is in this very sense that United States of Banana is quite literally a post-9/11 work. On that date, the melted and collapsed Twin Towers, symbols of capitalism and the old empire, made way for new values, and to that end, Giannina, who often appears to be more Nietzschean than even Zarathustra says: “The great event is the creation of a new value—a new value appears like a rainbow with many envelopes that shed mystery” (53, below).

United States of Banana: A Graphic Novel is a work of metamorphoses and of becomings, masterfully achieved through the image inspiring words of the iconic Latinx poet and radical thinker Giannina Braschi and the artwork of Joakim Lindengren, whose illustrations give them a bizarre and beautiful twist. Where Braschi parodies—always with utmost respect—the history of literature, Lindengren does the same with the history of art (classical and contemporary), and together they have created a book of words and images, an artefact, an event.

Rolando Perez

LATINX SPACES

Rolando Pérez is a contributor to Latin American Studies encyclopedias and anthologies (including the Oxford Handbooks) to which contributed sections, such as “The Bilingualisms of Latino/a Literatures” and Spanish-English Code-switching in Nuyorican and Caribbean literature. Pérez’s research pairs philosophers and writers on subjects or concepts in common. He publishes on the intersections of Latin American and Latinx literature and philosophy, including essays on José Martí, Alejandra Pizarnik, Gloria Anzaldúa, Giannina Braschi, Gustavo Pérez Firmat, and Severo Sarduy. He is collaborator with scholars in distinct research fields, including Ilan Stavans (Spanglish), Linda Martín Alcoff (feminist and Latin American/Latinx philosophy). His creative writing in Spanish and English consists of theater and prose poetry, including Tea Ceremonies in Winter, La comedia eléctrica, The Lining of Our Souls: Excursion into Selected Paintings by Edward Hopper, The Electric Comedy, and The Divine Duty of Servants. His stories and poems have been anthologized in the Norton Anthology of Latino Literature edited by Ilan Stavans and in The Hispanic Literary Companion edited by Nicolás Kanellos. He was a contributor to Poets, Philosophers, Lovers: On the Writings of Giannina Braschi, edited by Frederick Luis Aldama and Tess O’Dwyer (Pittsburgh, 2020). In past lives he has also been an actor and a pilot.

Other Interviews and Essays on Braschi’s Geopolitical Tragicomedy

- Stanchich, Maritza. “Braschi, Giannina.” The Encyclopedia of Contemporary American Fiction 1980–2020 1 (2022): 1-7.

- Riofrio, J. Falling for debt: Giannina Braschi, the Latinx avant-garde, and financial terrorism in the United States of Banana. Lat Stud 18, 66–81 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41276-019-00239-2

- Dabashi, Hamid. “On nations without borders.” Global Middle East: Into the Twenty-First Century 3 (2021): 60.

- Lowry, Elizabeth. “Rhetoric, Identification, and Symbolic Representation in Giannina Braschi’s United States of Banana.” Representing 9/11: Trauma, Ideology, and Nationalism in Literature, Film, and Television (2015): 155.

- Stanchich, Maritza. “Bilingual Big Bang,” Poets, Philosophers, Lovers, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020.

- Perisic, Alexandra. Precarious crossings: Immigration, neoliberalism, and the Atlantic. The Ohio State University Press, 2019.

- Franzway, Sam. “United States of Banana.” Transnational Literature 9.1 (2016): 1.

- Cruz-Malavé, Arnaldo Manuel. “” Under the Skirt of Liberty”: Giannina Braschi Rewrites Empire.” American Quarterly 66.3 (2014): 801-818.

- Garrigós, Cristina. “Giannina and Braschi.” Poets, Philosophers, Lovers: On the Writings of Giannina Braschi (2020): 20.