Putinoika analysis by Elidio La Torre Lagares

Putinoika as a dispositif

Braschi destabilizes the Western concept of classical narration, which constructs itself upon causal relations that arbitrate narrative propositions into an organized plot. In her discursive artifact (a Menippean satire, after all), Braschi splices the novel with the dexterity of a DJ, tracing voices and replicating them, assembling a cacophony of resonances and knowledges. These voices operate as dispositifs, simultaneously organizing and producing the textual body, a site of incessant movement where narration unfolds as an interplay of fragments rather than a linear trajectory.

On June 29, 1940, commemorating the sixty-fourth anniversary of its founding, the Ateneo Puertorriqueño organized a public forum on the cultural problems of Puerto Rico, structured into five sessions over two days. This event convened an illustrious intellectual cohort, as Vicens Géigel Polanco notes in the prologue to Problemas de la cultura en Puerto Rico: Foro del Ateneo de 1940, a work published thirty-six years later. Despite the ideological and academic divergences among the participants, one thematic thread remains constant across the thirty-nine presentations: the affirmation that Puerto Rico belongs to Western culture.

Within this register, Jaime Benítez, who inaugurates the interventions, underscores that Puerto Rico forms part of “a family—the Western household, from which we have nourished ourselves and continue to do so.” Similarly, Antonio Fernós Isern declares that Puerto Rican civilization is “fundamentally a Western civilization.” These echoes culminate in Luis Muñoz Marín’s essay, “Culture and Democracy,” where he attempts to reconcile the differences in what he calls “our Western minds.”

But the jest lies in believing the simulacrum. There is more mimicry and paint-by-numbers here than genuine curation of knowledge.

We are well aware that Western imposition was not only materially violent but also symbolically so. The devaluation of Indigenous and African cultures rendered us colonized “primitives” or “barbarians,” in need of order and domestication—a narrative that legitimized colonialism as a civilizing mission.

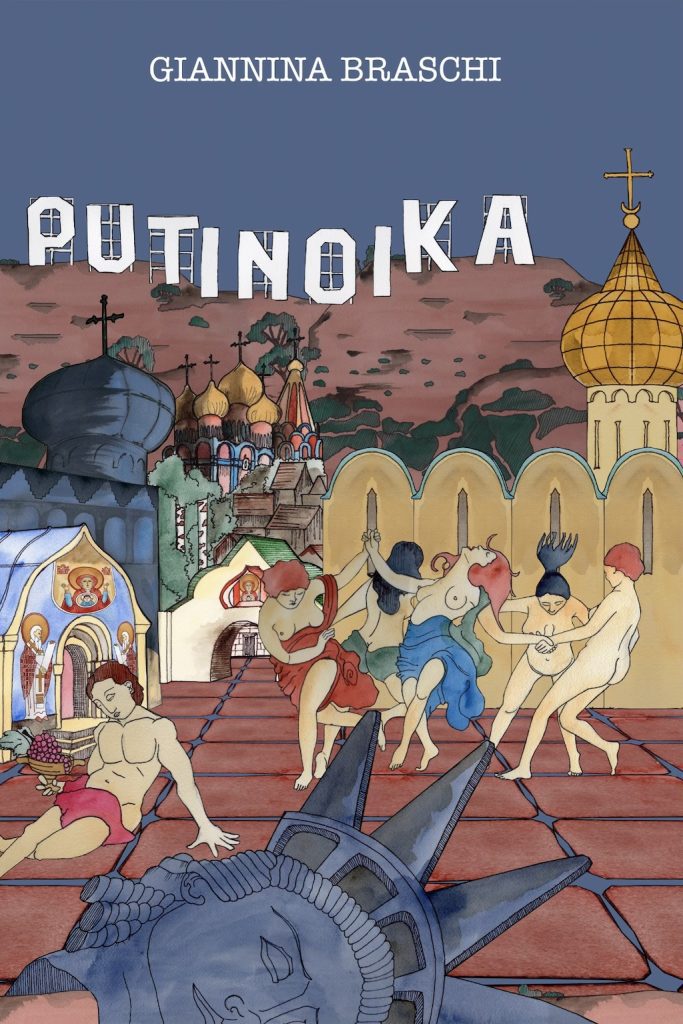

Eighty-four years after that Ateneo forum, the Avant-Rican writer Giannina Braschi emerges to domesticate the domesticators. In her latest work, Putinoika, the author of Yo-Yo Boing! and The United States of Banana annihilates the remnants of Western civilization’s ruins, and from that body without organs arises a creation resistant to conventional classifications, yet uncompromising in its critique of neoliberal policies, contemporary power structures, and the pernicious effects of dominant cultures. Through her masterful textual assemblage, Putinoika incorporates poetry, drama, and prose to craft a fluid and dynamic narrative landscape. Putinoika is neither novel, nor epic, nor drama: it is, in fact, an artifact that becomes a literary device operating on multiple levels, where language games, politics as simulation, hyperreality, and hyperglossia dominate.

The title Putinoika fuses the names Putin and Troika set as antipodes to the historic Perestroika of Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985. Perestroika is remembered as the ambitious, albeit failed, attempt to reform the crisis-ridden system of the former Soviet Union. Although the reforms fell short of their intended effects, they triggered a series of changes that transformed the global geopolitical landscape, such as the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, Germany’s reunification, and the end of the Cold War.

In other words, the narrative space becomes the Ground Zero of the simulacrum, where the historical antecedents—the American empire, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico (ELA), binary oppositions, and so on—dissolve into inconsequence.

From the outset, Braschi undermines the Western concept of classical narration, which relies on causal relationships to resolve narrative propositions into an organized plot. In her discursive artifact (a Menippean satire, after all), Braschi stitches together a novel with the skill of a DJ, sampling voices and replicating them like a box of resonances and knowledges whose devices operate as both organization and production of the textual body. The characters thus resemble intrusive spirits or “walk-ins” performing a cosplay of mythological figures and global personalities against the backdrop of contemporary politics and global crises, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic, which serves as both a terminus and a point of departure—a reset, so to speak.

Braschi’s text is like the music of the stars: it resonates and vanishes in vastness, where Oedipus, Antigone, and Eurydice interact with political figures like Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, while sampling everything from Tito Puente, Leonard Cohen, and Carol G to Greta Thunberg. In a parallel world, Putinoika becomes the matrix of The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot.

Irreducible and irrational, Putinoika functions as a Foucauldian dispositif activated by historical and contextual needs, operating here to (de)regulate obedient placidity and (re)invert power relations. For this, Braschi’s writing demands lucidity in handling what, on a formal Sunday afternoon, might pass for conspiracy theories—or, as the character Ivania (Trump) quips in the novel, “Fake is the new truth.”

In Putinoika, reality becomes inaccessible. The saturation of signs and the loss of what Baudrillard calls “the real” are replaced by reproductions, falsifications, and distorted versions confused with authenticity, punctuated by Tiresias’s declaration: “I invented fake news.” Divided into three sections—Palinode, Bacantes, and Putinoika—the text presents a gallery of intertextual and intertemporal dialogues where diverse voices (many elusive even to the most discerning reader) critique the hegemony of political power, reflect on cultural and financial debts, and explore the futility of human struggle under systemic oppression.

Braschi’s Putinoika demands the seriousness of humor and irony to articulate its philosophical reflections. Through this, she advances her ruthless critique of Western civilization and its monological, phallocentric, paternalistic, and colonizing practices, assumed and contested by the Putinas—the triad (the Troika) composed of Melania, Ivania, and Ivanka Trump, who operate as narcissistic agents of Putin. In this way, the text orients the reader’s experience, generating meanings concerning cultural, historical, and political contexts. Braschi’s literary artifact thus manages, modulates, or subverts the flow of significations and powers within the work. In the process, the hybridization of genres emerges as a justified (almost desperate) strategy of resistance to literary norms and sociopolitical structures, dismantling the structural comforts of the classical realist novel.

The disruptive poetics of Braschi reveal how language and narratives operate within power systems to legitimize or challenge ideological structures. Hence, all that can be encoded in language harbors the potential for deception. In this sense, Braschi’s writing becomes a device in itself: a textual machine that both reflects and resists the cultural and political mechanisms it critiques.

In Putinoika, the dispositif exceeds mere control functions, encompassing a productive capacity that overflows into a proliferation of meanings—a manifestation of what I insist on calling hyperglossia, where the text surpasses its own boundaries to generate an expansive network of ceaselessly moving signs. Thus, the causal argument pattern is displaced by one of movement, driven primarily by the affective sense that precedes the text. The Braschian device, then, is neither static nor monolithic; it is a fluid mechanism adapting and mutating as the text unfolds, dismantling colonizing discursive hierarchies.

By hyperglossia, I refer to the overflow of the text beyond its textual space or the influx of “uncontainable data” that magnifies reality through textual reproduction in parallel with contextual forces. Braschi’s use of multiple rhetorical registers—from philosophical discourse to satirical critique—creates a constant oscillation between the text and its sociopolitical contexts. This dynamic interaction aligns with Braschi’s amplification of reality through hyperbole, which is nothing less than reality exaggerated and magnified, revealing, in its satirical form, an alternate reality that underlies it.

Ultimately, Putinoika exemplifies a conscious notion of infinity central to hyperglossia, as its narrative unfolds through continuous changes in form and discourse, creating networks of incessant signification, akin to traversing the striated paths of cyberspace. Through perpetual reconfiguration via mythological, historical, and contemporary allusions, the Braschian artifact operates as a network of perpetually moving and interactive signs.

Yet, despite its voices and noise, Putinoika contains the resounding silence of compositional instability, most evident in Braschi’s deliberate disruption of conventional narrative closure. Instead of resolving into a unified totality, Putinoika remains in a state of decompositional flux. Once again, its hybrid form resists containment. This textual instability exemplifies hyperglossia’s capacity to deconstruct and reproduce rhetorical instances, constantly reassembling them into new discursive formations. Therefore, Braschi’s hybrid writing is not merely a stylistic choice but a potent method of decolonizing literature. Employing linguistic play that resists traditional syntax and grammar—those other forms of cultural domination—Braschi’s work exposes and dismantles the systems of power embedded within language.

At the heart of Putinoika lies the exploration of tyranny and oppression, embodied in the figures of Trump and Putin, who dominate the text and epitomize humanity’s failures. Braschi’s representation of these figures is both satirical and critical, exposing the absurdity and danger of their authoritarian tendencies.

Braschi wields satire as a weapon of resistance with morbid precision. For instance, in a particularly memorable scene, the character Antigone rejects paying a debt she does not owe—a clear metaphor for how Puerto Rico’s colonial administration burdens its citizens with the consequences of corrupt leadership. Similarly, Braschi’s portrayal of Trump’s America becomes a biting indictment of capitalism, presented as exploitative, corrupt, and ultimately self-destructive. References to golf courses, tax evasion, and consumerism underscore the emptiness of the American Dream, which Braschi exposes as little more than a façade for greed and inequality.

Ultimately, Putinoika defies simplistic interpretation, much like the world it seeks to critique. Its hybrid form opens up a philosophical depth that transforms it into a powerful work of literary resistance that compels readers to question the systems of power governing our lives. As the narrative fades into clarity, it suggests that literature retains the power to resist, subvert, and ultimately liberate us—to make us anew.

It is, finally, the hope for something better that endures.

Putinoika analysis in Spanish

- Putinoika analysis by Miguel Angel Zapata en Latino Book Review.

- Putinoika analysis by Inmaculada Bonilla in ZENDA.

- Putinoika analysis by Carmen Dolores Hernández in Nuevo Dia

- Putinoika analysis by Mario Alegre Barrios.

- Putinoika analysis by Patricia López Gay in Nueva Revista.

- Putinoika interview by Sandra Guzmán in World Literature Today.

- Putinoika analysis by Sophia Yip for Latinx Pop Magazine.