Antigone Philosophy Poetry Theater: a blog post featuring the poem “Antigone” by Giannina Braschi in Poetry Magazine.

Antigone

Antigone: Anti what is gone. If it leaves, it’s for a reason. Anti has to be gone. It has to go. It always goes against. Against the state— against kinship—and against myself. I don’t want to be the anti-clash. Anti has to go from gone. Gone has to leave immediately, without pause, without cause. I can understand the arguments that defend gone—but they always delay my stay on this planet. They come with Anti—as a pre-position— and they make me stay in Antigone—anti what leaves—what speeds—what argues against. Why can’t I argue in favor of gone? Go by and pass away—if you can’t stay for a moment— without hesitation—blaming me for a crime—if you can’t stop victimization—if you can’t say something without struggling against the gone of another antagonistic element. Why the agony of the anti and the gone? I’ll make a drama of myself in two parts.

Anti: Always against. Versus must always keep up a fight. I wish they could stop fighting—two at a time—as if the contradiction of themselves could make each one of the antagonistic elements find a commonality that makes them advance and not nix each out again, denying their positive energies.

Gone: Please. Gone with the wind. Anti has to go. It cannot last forever having to contradict itself always—and not getting ahead—because it is anti-getting forward.

Anti: If I were not against all the gones, how many more gones would have already left us—and we need more voices here to argue against all that has to leave— because you say it is gone prematurely—you say it has to be gone—but I am Antigone—against what leaves prematurely. And why does it have to leave? Why can’t it stay here forever? Antigone means to stay. Don’t leave us orphans of your anti. We want to be Antigone—anti what is gone forever. Committed to the everlasting changes of humanity as a swarm, a horde, a chorus, a proliferation, and a multiplication of all the ones that are anti what is gone.

Gone: If it is gone with the wind—it is better than if it stays without a reason to stay.

Anti: I am the primary beneficiary. I exist as an anti—what is gone. And I like myself as an anti that exists with gone. Don’t let me die because you want to move forward without me. Things should not be defined any longer. What has to be valued is the growth—and the process in which things develop by themselves. Don’t take away the possibility of growth by cutting a definition short of growth—of process. The development of a thing is more important than the definition of a thing.

Gone: Go to another name and unite with another past participle. But don’t keep me up fighting all night with kinship—with the state—with myself—existing with protests inside—always protesting inside me—as a public manifestation of being buried alive in Antigone— who doesn’t let me go—but keeps me struggling to survive. Good vibes—bad vibes—this is what I am feeling all the time. Let bygones be bygones. But anti doesn’t allow a good-bye. Bye-bye. It always inserts the bad vibes inside the good-bye. With all the protests against bye-bye. Let me tell you how happy I am being gone, bye-bye.

Good-bye: Let me speak for myself as a lullaby, good night.

Bad Vibes: With Gone there are always protests from Anti-gone. I am happy she is still here with us as an argument of pros and cons— and as a contradiction that wants to rest eternally in a mausoleum with us.

Anti: It is the body politic persisting, insisting it has a body of work and muscles to train—and trains to catch— and it wants to rise in love—and raise humanity to a higher quality of itself—and it doesn’t want to leave us without a body of work to complete its masterpiece. Don’t even try to take Antigone from gone. Anti is the body of work that doesn’t want to leave everything unfinished before it is time to go away. And when gone comes to take anti away from body—body will manifest itself as a protest of antagonism—and contradiction— contrasting gone with the spirit of rain and wind —and flesh with earth and fire. Here, keep the torch alive!

Antigone: profound new work of Latinx philosophy, poetry, and theater

Poetry magazine featured Giannina Braschi’s poem “Antigone” along with an interview with the Latinx poet and philosopher called “A Big Solitude.” Poetry has also published “In Colorado My Father Scoured and Stacked Dishes” by Eduardo C. Corral; Citizen by Claudia Rankine; “Vulnerability Study” by Solmaz Sharif; “alternate names for black boys” by Danez Smith; and “Aubade with Burning City” by Ocean Vuong. Recent issues have featured poems by Toi Derricotte, Carolyn Forché, Terrance Hayes, Juan Felipe Herrera, Jamaal May, Les Murray, Craig Santos Perez, and C.D. Wright.

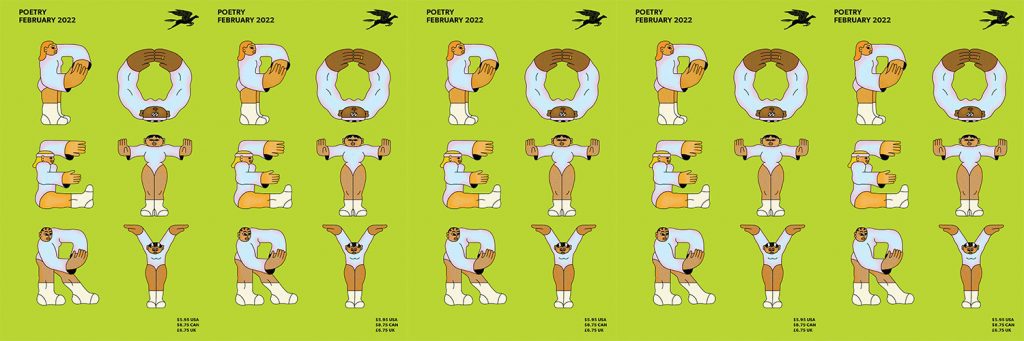

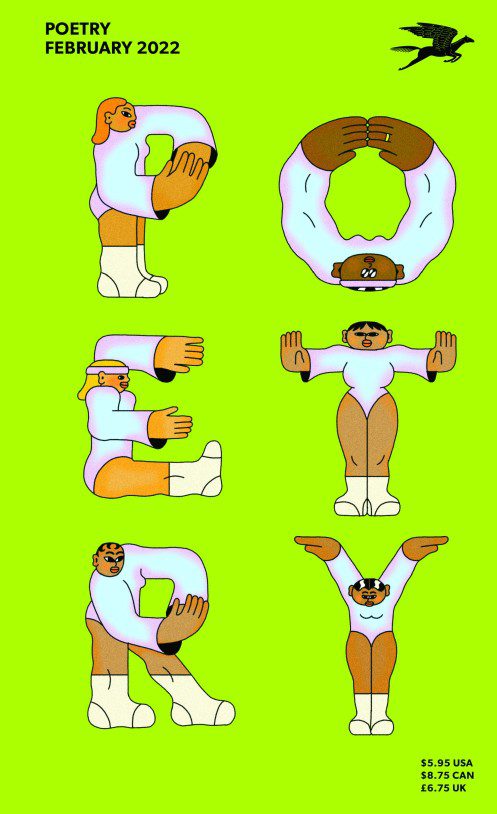

Poetry

Poetry Magazine Presents the Best of Contemporary American Poetry

Founded in Chicago by Harriet Monroe in 1912, Poetry magazine began with the “Open Door.” In its first year Poetry published Joyce Kilmer’s “Trees,” Ezra Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro,” William Carlos Williams, and William Butler Yeats and introduced Rabindranath Tagore to the English-speaking world just before he was awarded the Nobel Prize.

The magazine has since been in continuous publication for more than 100 years, making it the oldest monthly magazine devoted to verse in the English language. Perhaps most famous for having been the first to publish T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” (and, later, John Ashbery’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror”), Poetry also championed the early works of H.D., Robert Frost, Langston Hughes, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Marianne Moore. It was first to recognize many poems that are now widely anthologized: “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks, Briggflatts by Basil Bunting, “anyone lived in a pretty how town” by E.E. Cummings, “Chez Jane” by Frank O’Hara, “Fever 103°” by Sylvia Plath, “Chicago” by Carl Sandburg, “Sunday Morning” by Wallace Stevens, and many others. Elizabeth Bishop, Charles Bukowski, Raymond Carver, Allen Ginsberg, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and Tennessee Williams, to name just a few, have also appeared in Poetry’s pages.

Today, Poetry regularly presents new work by the most recognized poets, but its primary commitment is still to discover new voices: more than a third of the poets published in recent years have been new to the magazine. Translations are published throughout the year and in an annual translation issue to deepen readers’ engagement with foreign-language poetry.

Poetry is known for its enlivening “Comment” section, featuring book reviews, essays, and “The View from Here” column, which highlights artists, professionals, and others from outside the poetry world writing about their experience of poetry.

Recent installments have included pieces by cartoonist Lynda Barry; musician Neko Case; novelist and essayist Roxane Gay; author of the “Lemony Snicket” children’s series, Daniel Handler; the late columnist Christopher Hitchens; hip-hop artist Che “Rhymefest” Smith; artist Ai Weiwei; and philosopher Slavoj Žižek.

The February 2022 edition in which the poem Antigone by Latinx poet and philosopher Giannina Braschi appears was edited by Suzi F. Garcia. (Tags: Antigone philosophy poetry theater)