Algorithm of Beauty: Aesthetic Judgment as a Science

The Algorithm of Beauty

Aesthetic Judgment as a Science

A Companion to Literary Evaluation

Except #1: The Algorithm of Beauty

The word algorithm is the anglicized version of the name of Al- Khwârizmi, a Persian mathematician from the eighth century; the term was subsequently introduced into the English language in the twelfth century by the monk, Adelard of Bath. According to The New Penguin English Dictionary, it is “a systematic procedure for solving a

mathematical problem in a finite number of steps.” If an algorithm is relatively easily defined, this is not the case for beauty. Sadly, there is no space here to cite and probe the wealth of definitions of beauty that have existed from ancient times until the present day, from Aristotle’s Poetics (335 BC) to Terry Eagleton’s The Ideology of the Aesthetic (1990), to cite just two examples. However, some attempt must be made and will indeed

be done so in due course.

Let us start by asking whether beauty is truly in the eye of the beholder, as received wisdom would have it, thus rendering it perceptual and individual, in which case it would be incompatible with any kind of algorithm or, on the other hand, whether there is some abstract standard of beauty with distinct characteristics that can be reproduced,

by a machine, if necessary. Obviously, if we wish to create an algorithm, we must incline to the latter opinion. Indeed, would it not be possible to discern a formula for beauty, whether it be in Monet’s series of water lily paintings, in the work of Picasso’s blue period, in Shakespeare’s sonnets, in Schubert’s piano concertos, or in George Eliot’s novels? Or, does there remain some surplus element, some ungraspable and indefinable essence that is the hallmark of beauty and the product of genius that can never be reduced to a formula?

Excerpt 2: The Algorithm of Beauty

“Laying Bare the Device” and ostranenie

The above-mentioned Russian Formalists were the first to suggest the possibility of such technicity in literary analysis. As Tony Bennett points out, “they were united in their wish to establish the study of literature on a scientific footing, to constitute it as an autonomous science using methods and procedures of its own” (Bennett 1986: 19). The expression “laying bare the device” comes from Viktor Shklovsky. It denotes a preference for “literary forms which, rather than concealing or effacing their own formal operations, explicitly display on the surface the processes of their own working” (Bennett 1986: 25). It is closely linked to the concept of defamiliarization (ostranenie in Russian), the “making strange,” “slowing down,” or “prolonging” of perception which impedes the reader’s “habitual, automatic relation to objects, situations, and poetic form itself” (Shklovsky 1965: 12). It is hardly surprising that Laurence Sterne’s celebrated novel, The Life and Opinions of Tristram

Shandy (1759), often cited as exhibiting postmodern aesthetics before its time (see, for example, Pierce and de Voogd 1994), should have been chosen for study by Shklovsky.

Let us briefly make a foray into a few passages from a contemporary novel, which could also be classified as experimental and postmodern in its aesthetics, that is, self- referential, generically and stylistically hybrid, drawing on intertextuality to mix high and low cultural influences and to rewrite history in a playful manner. We could add, as well, its preference for the ontological dominant as opposed to the epistemological dominant, as set out in Postmodernist Fiction (1987), by Brian McHale, a critic in the Formalist and Structuralist tradition. His contention is that a postmodernist aesthetics raises questions pertaining to the mode of existence of a text rather than to the knowledge to which it might give rise.

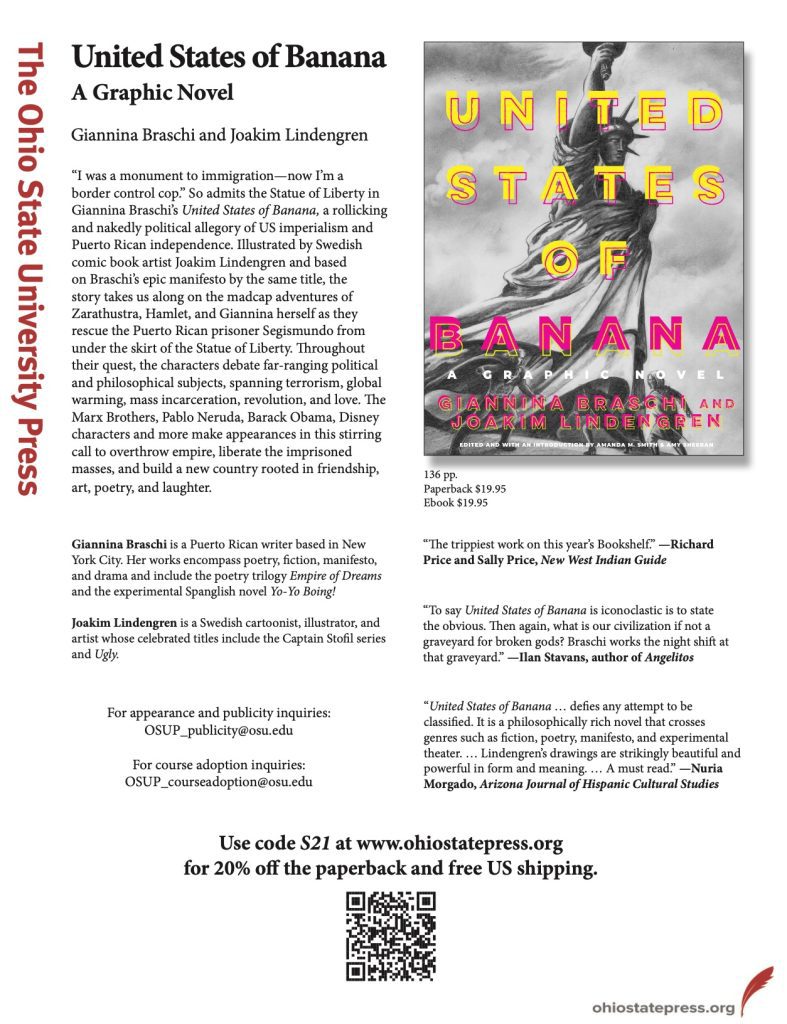

United States of Banana is a recent novel (2011), written in English and Spanglish by the Porto Rican writer, Giannina Braschi, who has been living in New York since 1977. It tells the story of the events of 9/11, seen through the eyes of the main protagonist, Giannina, and through those of the traveling companions whom she picks up on her journey south from the smoking ruins of the World Trade Centre to Porto Rico where she hopes to inaugurate a new age of liberty for the oppressed and the colonized. These fellow travelers include Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the seventeenth- century Spanish playwright, Calderon de la Barca’s hero, Segismundo from (Life is a Dream, 1639), the celebrated sardine from Goya’s painting, “The Burial of the Sardine” (1810), and also Plato’s Diotima and a taxi driver named Hasib, both of whom become part of Giannina’s informal Symposium with which the story ends. The novel is highly original on the level of language and form and is even described as “revolutionary” on the back cover. At first sight, it can prove something of a challenge to the reader, taking the form, as it does, of an epic poem, a play, a Socratic dialogue, a Platonic symposium, or simply an internal focalization on the discombobulated mind of the main protagonist, seemingly more traumatized by the workings of late capitalism than by the actual disaster of 9/11 unfolding in front of her eyes:

I used to hear the voices of the people in taxi drivers— but now their voices are hooked up to cell phones, iPods, or Blackberries. If you talk to them— they disconnect only for a second— and return to their gadgets. Human beings can’t bear very much reality. They need a prop in their hands. It used to be the cigarette. Everybody was smoking in the streets. And now they use electronics to formalize the fact that they’re busy with the dread of daily living that produces nothing creative but the monotony that they call pragmatism. They’re busy producing dust, frenemies, intrigue. They’re fire- breathing dragons foaming at the office of their mouths.

Giannina Braschi, United States of Banana

“They’re busy producing dust, frenemies, intrigue.” The syntax, which consists of either very short sentences or much longer ones interrupted by dashes, imbues the extract with a strong impression of fragmentation, reflecting the unsettling thoughts of the narrator. The internal rhyme of the last sentence and the alliteration in i convey the finality of a shocking and unexpected epiphany in which 9/11 is seen as a work of art. The reference to literary Modernism via the application to the digiverse of a line from part one of T.S Eliot’s “Burnt Norton,” “human kind/Cannot bear very much reality,” suggests a sophisticated aesthetic that challenges the banality of contemporary cultural clichés and allows the author to rewrite radical politics as high art. Poetic mastery creates a defamiliarized alternative to the symbolic poverty of consumer society.

At the same time, relationships of counterpoint, contrast, and parallelism are created between different words and lines, thus conferring a certain symmetry to the piece and allowing the reader to identify a method in its madness. Indeed, the strange beauty of the text can be teased out with the tools of stylistics and with reference to a Formalist method of analysis. We can see how a banal contemporary street scene has been turned into something strange and unrecognizable, which renews our perception and conveys important messages about contemporary reality. Such techniques constitute a certain style, characteristic of poetic language, which can be repeated, if not systematized, to form an aesthetic pattern or formula. The incipit is a case in point.

I saw a torso falling— no legs— no head— just a torso. I am redundant because I can’t believe what I saw. I saw a torso falling— no legs— no head— just a torso— tumbling in the air—dressed in a bright white shirt— the shirt of a businessman— tucked in— neatly— under the belt— snuggly fastened— holding up his pants that had no legs. He had hit a steel girder andhe was dead— dead for a ducat, dead. — on the floor of Krispy Kreme— with powdered donuts for a head, fresh from the oven— crispy and round— hot and tasty— and this businessman on

the ground was clutching a briefcase in his hand— and on his finger, the wedding band. I suppose he thought his briefcase was his life— or his wife— or that both were one because the briefcase was as tight in hand as the wedding band

(Ground Zero, United States of Banana)

The reader will notice the same techniques at play, for example, alliteration and internal rhyme. In this instance, the dash has the effect of slowing down the description of events, as if the reader were experiencing them in real time as they happen. The tone is at once ponderous, thanks to the consistent anaphora and repetition but also light and ironical in its choice of vocabulary, “snuggly,” crispy and round” and “powdered donuts,” all of which make reading the text a strange and defamiliarizing experience. Like Barthes’ steak and chips, the Krispy Kreme doughnut is a symbol of a contemporary myth, that of the American consumerist dream which has turned into a nightmare. A quote from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, “dead— dead for a ducat, dead,” is recycled to suggest a violent, topsy- turvy world where a briefcase, a life, and a wife are on a par, literally and metaphorically. By association, the businessman gets his just “desserts,” as it were, as does the “rat” in the play, in fact, poor Polonius, hiding behind the arras in the queen’s bedroom, and who is mistaken for the treacherous king and stepfather of Hamlet. Thus, instead of the recognition of the immensity of the event as unprecedented personal and collective tragedy that has appeared unfailingly in most post- 9/11 novels, Braschi’s narrator restages the catastrophe around a single grotesque synecdochic (a figure of speech in which a part is made to signify the whole) snapshot: “Death of the Businessman,” where the exploded torso of the victim represents the ultimate comic reification of humanity, consonant with the logic of materialism.

Barthes’s five codes of structural linguistic analysis could also be successfully applied to this incipit, starting with the hermeneutic code that posits the enigma of the text, in this case thanks to the shocking defamiliarization of the scene described: the violent death of a businessman dressed up as farce, the ghastly and grotesque image of a torso with doughnuts for a head.

It is difficult for the reader to know what to think or how to react at this early stage: should s/he be shocked, horrified, amused? What role will this deceased businessman play in the rest of the story? What about his wife? Does his briefcase contain important documents? Thus, we are presented with a series of unanswered questions that invite us to turn the page in our desire to know more and solve the puzzle. Indeed, according to Barthes, reading any piece of fiction is somewhat akin to reading a detective story. Barthes’ proairetic code refers to the sequential elements of action that build up narrative tension and suspense thanks to information furnished in a prescribed order, in this case, the falling to his death of the businessman.

In Greek, the word proairetic signifies the choice of one thing before another. This process in turn creates expectations in the reader and a narrative drive. What will happen next to the torso, the briefcase, or indeed the wife, and what will their significance be? The semic code is responsible for scattering overtones and clues beyond the literal connotation of words, constructing character through signifiers. Thus, the reader gets a picture of a slightly portly (“snuggly fastened”), smart (“bright white”) businessman and his life in which his job (the “briefcase” is mentioned three times in quick succession) seems as important as, if not more so, than his wife (“wedding band”), or indeed his life. The symbolic code concerns the larger structure of the text and manifests itself thanks to pairs or clusters of symbolic meanings, often based on oppositions that accumulate to confer a larger structure and meaning to the text. Here, for example, we can find an interesting contrast between the softness of the doughnut and the hardness of the steel girder, pain versus pleasure, and the exactions of capitalism and the self- indulgence of consumer society.

At the same time, on the symbolic level, the doughnuts, which are, to all intents and purposes, harmless objects, take on a sinister role, drawing attention to the price to be paid for easy consumerism and to the self- devouring, cannibalistic impulses of capitalism, perhaps. The cultural code refers to common bodies of knowledge, in this case, fast- food culture, business capitalism, the American work ethic, and marriage. By weaving together the five codes, a system of interpretation is constituted, and specific elements that might have been missed, glossed over, or ignored by a less technical reading of the text are made available for interpretation. All through the novel, the same poetic techniques are used in line with the Formalist creed of renewing perception. If the critic takes as his task the laying bare of the device, getting his hands dirty by performing the hard work of stylistic and structural linguistic analysis as a way to expose the mechanics of the text and its workings, a definite pattern can be discerned. Once identified, the recognition and understanding of this imperfect “algorithm” can help the reader to appreciate and comprehend what might at first sight appear impenetrable or confusing. Braschi, the novelist, has recourse to a “system” for producing beauty. Of course, it could be objected that this “system” is not precise enough to be fed into a machine to produce a work of art and it is this aspect to which we will now turn.

To read the full chapter, The Algorithm of Beauty, click here.

A Companion to Literary Evaluation

The first critical survey of its kind devoted solely to literary evaluation

Book Editor(s):Richard Bradford, Madelena Gonzalez, Kevin De Ornellas

Companion to Literary Evaluation bridges the gap between the non-academic literary world, where evaluation is deeply ingrained, and the world of academia, where evaluation is rarely considered. Encouraging readers to formulate and articulate arguments that balance instinctive judgment and reasoned assessment, this unique volume addresses key issues regarding literary values from the perspective of analytical aesthetics and the philosophy of literature.

Bringing together a diverse panel of contributors, the Companion explores competing theories of literary evaluation, the reasons for evaluating theater and lyric poetry in performance, the question of value in literary theory, debates over Modernism’s negative impact on literature, the possibility of evaluating aesthetic beauty through scientific and formalist methods, the nature and status of literary evaluation as a branch of criticism, aesthetics in applied and community theater, evaluation outside academia, the perils of extreme relativism and subjectivism in literary evaluation, evaluation in schools and much more. Contributors question and reassess the reputations of authors across the canon, from Shakespeare and James Shirley to T S Eliot, Kathleen Raine, Virginia Woolf, Joyce, Beckett amongst others such as Giannina Braschi. The Companion:

- Illustrates how divergent perspectives on the artistic qualities and value of literature can sometimes overlap

- Covers the standard range of literary genres, while including others such as unfinished novels, freelance journalism, and lyric poetry in performance

- Offers methodologies that demonstrate why literature can be treated as something different from other forms of language and therefore assessed as art

- Explores the importance of maintaining clarity and specificity in the evaluation of literary works

A Companion to Literary Evaluation is a must-read for undergraduates, research students, lecturers, and academics in search of fresh perspectives on standard literary critical issues.

The first critical survey of its kind devoted solely to literary evaluation

Companion to Literary Evaluation bridges the gap between the non-academic literary world, where evaluation is deeply ingrained, and the world of academia, where evaluation is rarely considered. Encouraging readers to formulate and articulate arguments that balance instinctive judgment and reasoned assessment, this volume addresses literary values from the perspective of analytical aesthetics and the philosophy of literature.

The Companion explores competing theories of literary evaluation, the reasons for evaluating theater and lyric poetry in performance, the question of value in literary theory, debates over Modernism’s negative impact on literature, the possibility of evaluating aesthetic beauty through scientific and formalist methods, the nature and status of literary evaluation as a branch of criticism, aesthetics in applied and community theater, evaluation outside academia, the perils of extreme relativism and subjectivism in literary evaluation, evaluation in schools and more.

Contributors question and reassess the reputations of authors across the canon, from Shakespeare and James Shirley to T S Eliot, Kathleen Raine, Virginia Woolf, Joyce and Beckett to Giannina Braschi.

| Name | Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture (Algorithm of Beauty) |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Wiley-Blackwell |

Key words: The Algorithm of Beauty, United States of Banana, Postmodern fiction, postmodernism, postmodern novel, map of Literature postmodernism, Puerto Rican literature, contemporary American novelUnited States of Banana