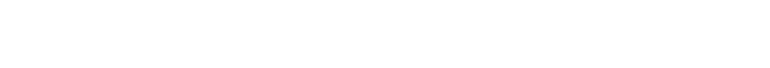

World Literature Today Reviews Putinoika by Giannina Braschi

Putinoika. Giannina Braschi. Flowersong Press. McAllen, Texas: 2024.

World Literature Today Book Review:s

PUTINOIKA

Reviewed by Carlos Labbé

From its title, Putinoika, the fourth novel by Puerto Rican writer Giannina Braschi, delivers some of the most urgent literature imaginable. Against the crushing waves of an endless despair-inducing ocean of news, it offers sailing it over pure textual delight—the here and now of wordplay, the release of hilarious dialogues, a slowly reveal of literature as a treatise of epistemology to oppose the banality of evil.

There is the sheer pleasure of witnessing a character called Bacchus talking with antagonists named Melania, Ivanka, and their husband. There is a secret group of women called the Putinas who infiltrates classical mythology to argue with the Furies to finally push Medea, Antigone, Clytemnestra and their peers to take charge. Also, the author herself appearsunder her own name or masked as Teiresias, Nietzsche, Greta Thunberg and countless other voices, to savor the joy of calling the President who hates the Spanish language a “Pendejo” a thousand times, simply because he lacks the capacity to recognize when he is being irrelevant in the realm of beauty. “The method of your madness is not precise,” adds the voice of Bacchus, also addressing the fact that this novel was originally written in English with crucial interpolations of slurs in Spanish. “You don’t have what it takes to make humanity tickle again,” as the ancient god of trickery pinpoints to remind the reader that the classics used to be part of a flammable civic debate before being sculpted in marble. Accordingly, this shapeshifting of a novel celebrates the grand tradition of searching for wisdom in dark times through the lens of mischief rather than tragedy. The echoes of its title also make its title a Paranoica novel, circling back to its obsession with Troika. Add to this the layer of the implicit Russian oligarch name reference—one that, in Spanish, hints at the “world’s oldest profession,” the one you are likely smiling about when reading the title: the profession of dominating while letting oneself be governed by the sum of money.

How does one grasp, in the deep urgency of Giannina Braschi’s narrative project, the importance of the out fashionedword perestroika embedded in the title, except as a denunciation of today’s inability to articulate a collective––nation-wide––will for radical openness? A society that once clenched shut like a fist for decades now sees communism, capitalism, and social democracy as interchangeable practices, wielded by authoritarian oligarchic groups for convenience. Can reality be manipulated simply by renaming things via government decree? Is not the act of writingpolitical literature in itself the opposite of totalitarianism —an unstoppable power over reality? Putinoika defies the logic of weaponize everything by offering, generously, a deep sense of belonging through the beauty of words—a beauty available to anyone whose only residency papers are this novel in their hands, the possibility to migrate freely into the joy of creation through collective listening and reading. Braschi proposes a strategy for survival in response to the rhetorical aggression of U.S. media and omnipresent power, akin to how Palestinian poetry, Ukrainian fiction, or Boricuareggaetón, confront genocide: before disappearing, let’s take inventory—a palinode of what still makes us happy among death threats, a bacchanalia of what is being taken from us, an orgy with all the materials that once defined what we called culture of life. “We can’t discover love in the patterns of disintegration of senses and control,” as the character Giannina declares.

“They think it’s all about storytelling,” she says earlier in the novel. “But I say it’s about geometry and architecture”. When Putinoika explores different strategies to deceit power, it also interrogates the nature of narrative itself. In a moment of bot farms, when the political event is a never ending rally of propaganda, the exposed polyphonic nature of Braschi’s book––to the point that it can be read as a theater play as well as an essay on freedom––asks aesthetically relevant questions: Is a novel just a monologue that erases the name of its characters, a disembodied stage––which also reminds contemporary chief oeuvres like Jon Fosse’s and Diamela Eltit’s––a tragedy without resolution, no catharsis in sight, just a constant buildup?

When “Language controls thinking process through plot,” liberation of the body in apparent madness seems like the realism of the current era, bringing to the front the perils of a novel without a story but made of myriad of fake narratives, in search of voices that can only offer truth when becomes an interrogatory:

I want the manifestation of the thinking process to express itself loud and clear––not to be subjugated to any past tense method but to clear its throat of any method to express its voice––the singing of its voice loud and clear––and the being that has been subjugated to the language––to the citizen––to the nation––to the system––to the method––to liberate itself from the shackles that contain a estructure.

If plot is everything, voices are also at risk of becoming mere puppets. Then, Braschi, asks, is there such thing as creativity freedom? Bacchus, her own version of Bacchus, responds: “I am pregnant with a chorus […] The masses want to become godly.”

At the launch of Putinoika in Manhattan during the fall of 2024, I raised my hand to ask a question: “Giannina, aren’t you afraid that Putin might read your novel, that his local agents might retaliate against you?” What I witnessed in her response—and this is why she is one of the living masters of Caribbean literature—was how her performance seeks to transcend notions of difference, rejecting literary indifference in favor of a quest for all sorts of universal justice. Following the hidden tradition of the best picaresque, trickster, prophets, her answer captured the zeitgeist as a mystery that everybody understands “It’s Putin who should fear me. Because what I do—my language, my work, my art, this literature that belongs to everyone—is something neither he nor his Putinos will ever be able to achieve or exploit to their advantage.”

“Giannina, aren’t you afraid that Putin might read your novel, that his local agents might retaliate against you?” What I witnessed in her response—and this is why she is one of the living masters of Caribbean literature—was how her performance seeks to transcend notions of difference, rejecting literary indifference in favor of a quest for all sorts of universal justice. Following the hidden tradition of the best picaresque, trickster, prophets, her answer captured the zeitgeist as a mystery that everybody understands “It’s Putin who should fear me. Because what I do—my language, my work, my art, this literature that belongs to everyone—is something neither he nor his Putinos will ever be able to achieve or exploit to their advantage.”

World Literature Today Reviews Putinoika

https://www.instagram.com/p/DChQWLpOyKB

Tags: WLT Book Reviews 2025, World Literature Today Reviews Putinoika, World Literature Today Reviews Giannina Braschi, a modern Bacchae, World Literature Today Book Reviews 2025, Putinas of Putinoika, Putinoika, Putinas of Putin